With a second wave hurting Europe and the numbers getting worse again in the US, this is not a post I wanted to write. During the first wave many schools closed and a lot of teachers had to move online. This was a gigantic effort, but now the first studies are coming in and the results can feel depressing. I want to discuss 3 studies that aren’t based on predictions but on actual data and end with both a kind of consolation and a warning.

A couple of weeks ago this study was published by Joana Elisa Maldonado and Kristof De Witte showing that the lockdown and the closing of schools for 2-3 months resulted in a quite huge drop in quite:

This paper evaluates the effects of school closures based on standardised tests in the last year of primary school in Flemish schools in Belgium. The data covers a large sample of Flemish schools over a period of six years from 2015 to 2020. We find that students of the 2020 cohort experienced significant learning losses in all tested subjects, with a decrease in school averages of mathematics scores of 0.19 standard deviations and Dutch scores of 0.29 standard deviations as compared to the previous cohort. This finding holds when accounting for school characteristics, standardised tests in grade 4, and school fixed effects. Moreover, we observe that inequality within schools rises by 17% for math and 20% for Dutch. Inequality between schools rises by 7% for math and 18% for Dutch. The learning losses are correlated with observed school characteristics as schools with a more disadvantaged student population experience larger learning losses.

The lockdown in the Netherlands was more a lockdown light, but the schools were also closed for 8 weeks. A second study by Engzell, Frey, and Verhagen shows the effects and again, those are not good:

Suspension of face-to-face instruction in schools during the COVID-19 pandemic has led to concerns about consequences for student learning. So far, data to study this question have been limited. Here we evaluate the effect of school closures on primary school performance using exceptionally rich data from the Netherlands (n≈350,000). The Netherlands represents a best-case scenario with a relatively short lockdown (8 weeks) and a high degree of technological preparedness. We use the fact that national exams took place before and after lockdown, and compare progress during this period to the same period in the three previous years using a difference-in-differences design. Our results reveal a learning loss of about 3 percentile points or 0.08 standard deviations. These results remain robust when balancing on the estimated propensity of treatment and using maximum entropy weights, or with fixed-effects specifications that compare students within the same school and family.

Do note that most schools in the Netherlands did their best to deliver distant education, most often online. This loss seems less big, but do note that this is a best-case scenario. But just as with the Belgian study, there is a big catch at the end of the abstract:

Losses are up to 55% larger among students from less-educated homes. Investigating mechanisms, we find that most of the effect reflects the cumulative impact of knowledge learned rather than transitory influences on the day of testing. The average learning loss is equivalent to a fifth of a school year, nearly exactly the same period that schools remained closed. These results imply that students made little or no progress whilst learning from home, and suggest much larger losses in countries less prepared for remote learning.

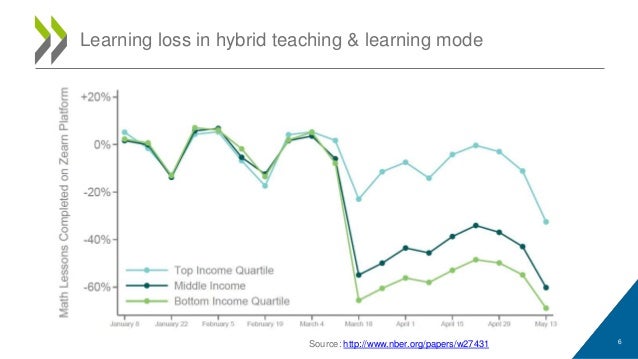

In my talks for ResearchEd @ home I warned for corona resulting in the differences between pupils getting bigger, and how I wanted to be wrong. Sadly, this seems not to be the case. For the third study, we move across the Atlantic. A study published by the NBER, written by Chetty et al contains the following graph:

To understand what the figure is showing, here is a short explanation:

We construct this series using data from Zearn Inc. at the class-week level, which we aggregate to the national-weekincome level according to the median household income of the Zip codes of Zearn schools (weighting by the average number of students using the platform at each school during the base period). The key outcome is student progress, defined as the number of accomplishment badges earned in Zearn in each week, relative to the base period of January 6th-February 7th. Our sample includes all classes with more than 10 students using Zearn during the base period, excluding those with fewer than five users in all weeks. We index student progress to pre-COVID student progress by dividing weekly progress at the school level by average weekly progress during the base period and then subtracting 1 to center the data around 0% change.

In this graphic, you see again the widening between different groups, with also the children of middle-class families being hurt a lot.

There are several reasons why we should be worried and feel depressed reading this. I know how much effort a lot of schools, teachers, and parents have put in trying to have some kind of education for their children in desperate times. We can only suspect that the results of doing nothing would have been way worse. But still, it’s not giving us much hope for the coming months.

It’s also some kind of warning for people hoping for a digital revolution in education. The past 7 months weren’t online or hybrid education at it’s best. This kind of teaching and learning needs a thorough preparation, which was most of the time not the case. But this won’t also be the case when things start to get a bit back to normal, as teachers are still struggling to get things done. One other confounding element will be gone, for a lot of children, there will be fewer worries about the virus, although the stress of a worsened economic situation for again the poorer families will probably remain.

There are more warning signs that the differences between families and children are getting worse, with Dirk Van Damme warning this week at the G Stic conference for a fastening trend of rich families looking for more commercial alternatives of extra tutoring or schooling as parents feel that the regular schools aren’t able to deliver what they think their children need.

We are facing some huge tasks in the very near future, and I’m convinced that long after we – hopefully – have a vaccine and when corona starts feeling like a bad dream that once happened, we will still see the consequences both in education and in society, for sure for low-income families and maybe even for families from the middle class.

[…] previous post on what the effect on learning has been of the different school closures around the gl… has gone a bit viral. A reaction I’ve heard before is that while the schools were closed and […]

[…] there are some studies – as discussed by Pedro de Bruyckere here – that indicate that, based on scores on standardised tests a) we’re dealing with quite a […]

[…] talk Martin and I had, was inspired by this post and this […]

[…] of the most-read posts on this blog the past few weeks was on the effect the pandemic has had on education. Bottom-line of the 3 studies I mentioned in that post: the online learning didn’t have the […]

[…] online classes during lockdown in this Covid-pandemic to bigger differences between pupils, e.g. here and here. This new study describes a similar trend in higher education – in line with earlier […]